The Indian Independence Act: A Contract That Scripted History

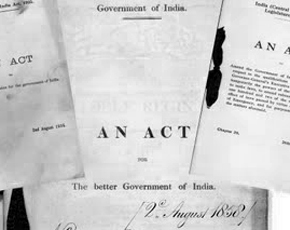

The Indian Independence Act of 1947 marked a pivotal moment in the history of the Indian subcontinent, signifying the culmination of the region’s long-fought struggle for self-determination after nearly two centuries of British rule (Geck, 2017). This political document, which outlined the terms and conditions under which British rule would end, bore striking resemblances to a contract.

The Act not only granted independence to India but also set the stage for the creation of the new nation of Pakistan, a consequence that would have far-reaching implications for the region (Geck, 2017) (Ali, 2003).

The contractual nature of the Act can be interpreted in various ways. The Act can be seen as an offer from the British Crown to relinquish power over India, with the acceptance of this offer being implicit in the formation of interim governments in both India and Pakistan. While the concept of consideration in a traditional contract is not strictly applicable, the Act can be viewed as a bargained-for exchange, where the British government, in exchange for relinquishing power, secured a swift exit from India, avoiding potential prolonged and costly conflicts (Geck, 2017).

The Act contained explicit terms and conditions, including the partition of British India into two dominions, India and Pakistan, based on religious demographics. This decision, which was influenced by the growing tensions between the Hindu and Muslim communities, would have far-reaching consequences for the region (Geck, 2017)(Shaikh et al., 2018).

The interpretation of the events preceding the establishment of the two separate Dominions of India and Pakistan has often been subject to various perspectives, with some attempting to justify or condemn the decisions and policies of the past (Hardy et al., 1985). Nonetheless, the Indian Independence Act of 1947 was a pivotal moment in the history of the subcontinent, marking the culmination of the nation’s long-fought struggle for self-determination and the beginning of a radical democratic experiment in South Asia (Geck, 2017).

The Contractual Nature of the Act

- Offer and Acceptance: The Act can be interpreted as an offer from the British Crown to relinquish power over India. The acceptance of this offer was implicit in the formation of interim governments in both India and Pakistan.

- Consideration: While the concept of consideration in a traditional contract is not strictly applicable, the Act can be seen as a bargained-for exchange. In exchange for relinquishing power, the British government secured a swift exit from India, avoiding potentially prolonged and costly conflicts.

- Terms and Conditions: The Act contained explicit terms and conditions, including:3.1 Partition of India: The Act divided British India into two dominions, India and Pakistan, based on religious demographics. To determine the exact boundaries between India and Pakistan, the Boundary Commission was set up, headed by Sir Cyril Radcliffe. The Commission had a short timeframe and faced immense pressure to deliver a verdict. The resulting borders were often arbitrary, leading to further displacement and violence.

3.2 Dominion Status: Was a constitutional position within the British Commonwealth which gave the India & Pakistan (East & West) the framework and ability for self-governance, and form its own governments under Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru & Liaquat Ali Khan, respectively. They would be responsible for making laws and policies, as well as the ability to conduct their own foreign relations and diplomacy. The British monarch’s role was largely ceremonial, and dominions were considered members of the voluntary British Commonwealth association. In essence, dominion status was a step towards complete independence, providing a bridge between colonial rule and full sovereignty.

3.3 Constitutional Framework: The Act provided a temporary constitutional framework for the interim governments until permanent constitutions were adopted.

3.4 Division of Assets: The Act outlined the division of assets, liabilities, and armed forces between the two dominions.

- Financial Assets: The division of the Reserve Bank of India, currency, gold reserves, and other financial assets was a major challenge. A complex formula was devised to allocate these resources between the two nations.

- Physical Assets: This included the division of government buildings, railways, post offices, and other infrastructure. The process was often arbitrary and led to disputes between the two countries.

- Debts: The allocation of debts, both internal and external, was another contentious issue. Both nations claimed a larger share of assets and a smaller share of liabilities.

- Princely States: The Act stipulated that princely states would have the option to join either India or Pakistan.

The major princely states that joined India included Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore (later Kerala), Jammu and Kashmir, Gwalior, Indore, Bho pal, Baroda, Cochin, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Udaipur, Bikaner, Patiala, Bhavnagar, and Junagadh (Geck, 2017). The states in the central, southern, and eastern regions of the subcontinent predominantly opted to accede to the Indian Union (Geck, 2017). In contrast, the princely states that joined Pakistan were located in the western and northwestern regions, including Bahawalpur, Khairpur, Kalat, Swat, Dir, and Chitral (Geck, 2017).It is important to note that the hundreds of smaller princely states that existed at the time of partition also joined either India or Pakistan based on factors such as geographic proximity, the religious affiliation of their rulers, and other local considerations (Geck, 2017). - Division of Armed Forces

3.4.5 (i) The Partition of the Army: The Indian Army was divided between India and Pakistan based on religious affiliations. This led to the creation of the Pakistan Army.

3.4.5 (ii) Naval and Air Forces: The Royal Indian Navy and Royal Indian Air Force were also divided, although the process was less contentious than the army’s partition.

While the Act appeared to be a contract, it was inherently imbalanced. The British, as the dominant party, dictated the terms, leaving little room for negotiation. India and Pakistan were essentially presented with a fait accompli, with limited options to modify the terms. The Indian Independence Act, despite its coercive nature, shares many characteristics of a contract. It established the framework for the transfer of power from British to Indian hands. However, the unequal power dynamics between the parties and the far-reaching consequences of the Act underscore the complexities of this historical agreement.

References

- Geck, C. (2017, July 1). The World Factbook. , 19(1), 58-60.

- Ali, T. (2003, January 1). The Untold and Alternate Story of the Indian Subcontinent’s War of Independence. Brill, 2(1), 37-61.

- Shaikh, I A., Islam, A., & Jatoi, B A. (2018, April 28). Bureaucracy: Max Weber’s Concept and Its Application to Pakistan. , 6(4).

- Hardy, P M., Hasan, M R., Kabir, H., & Chaudhuri, N. (1985, December 1). Four Opinions about the Partition of India. SAGE Publishing, 14(6), 40-41.

- Radcliffe Line was Declared as a Boundary Between India and Pakistan on 17th August 1947 – This Day in History – BYJU’S

- Partition of India | Summary, Cause, Effects, & Significance – Britannica

- Independence Day: How India & Pakistan divided money, assets, a buggy and a trombone

- Independence and Partition, 1947 | National Army Museum