The Copyright Row over Pop Artist Andy Warhol’s Paintings of Prince

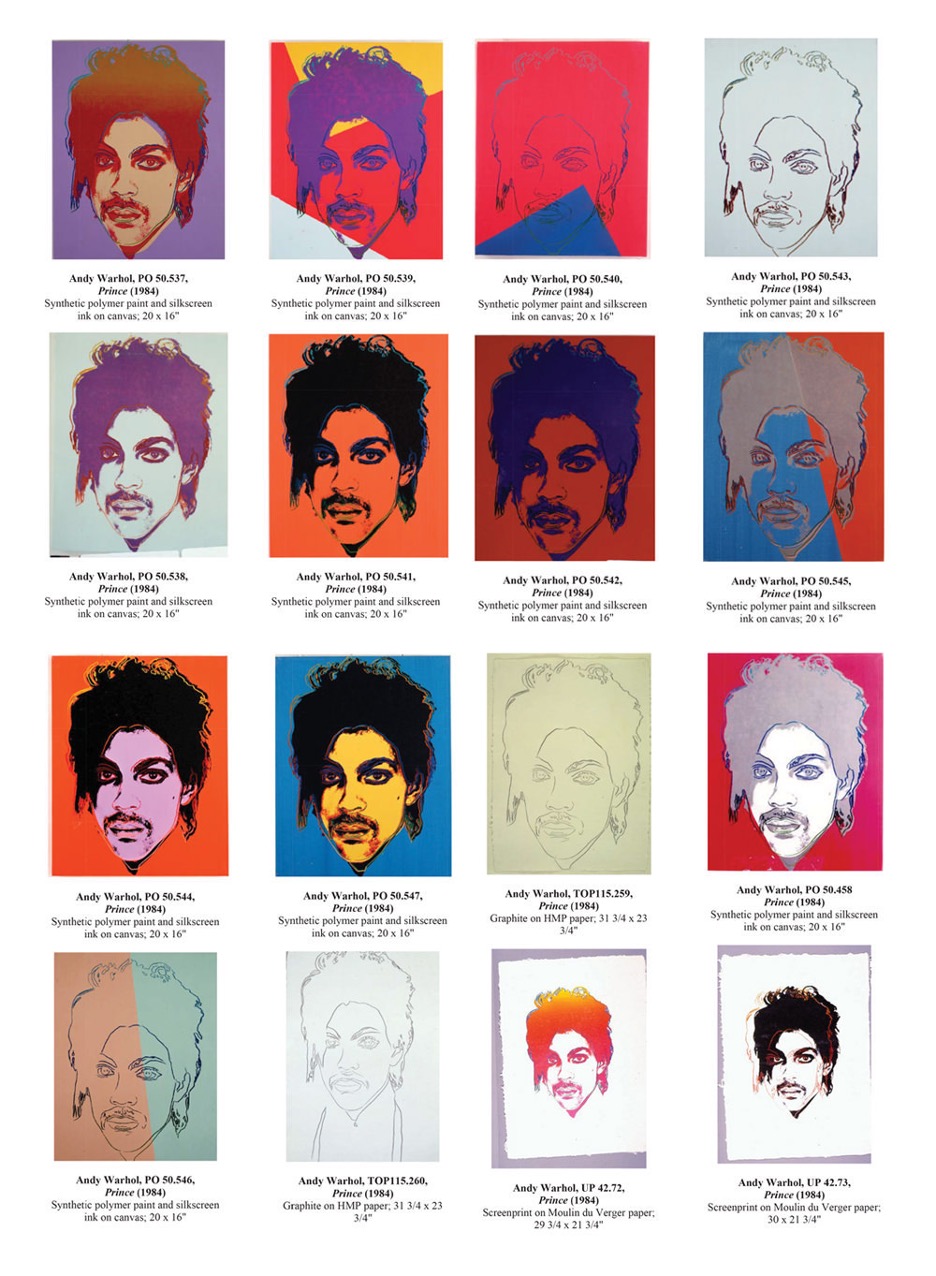

Andy Warhol Foundation actively supports the progress and growth of visual art through an artist-centred grant program. Their aim is to inspire and motivate the production of original works which leads to the enhancement of the contemporary art world. The Prince Series includes 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil illustrations, where Goldsmith claimed that everything happened without her knowledge and she came to know about these allegations of copyright infringement when Prince passed away in 2016 and Vanity fair utilised one of Warhol’s versions for their memorial cover for the singer.

Recently, the Second Circuit stated that the use of “Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph” by artist Andy Warhol to make 15 new unsanctioned silkscreen and pencil artworks which were not fair use. This decision of the Second Circuit has led to tremendous assumptions about the legacy of Andy Warhol and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts or commonly known as the “Warhol Foundation”, being Warhol’s successor, controls the copyrights.

On one hand, the court did not positively acknowledge the infringing works, but on the other hand, this decision with additional findings of the court that the works of Warhol are “substantially similar” to the original Goldsmith Photograph, all point toward an infringement if the case goes back to court for further adjudication. A number of Warhol’s works have pointed to appropriate third-party pictures without any licence, this could lead to any amount of litigation. The Warhol Foundation has filed an en banc petition for a panel to review the decision. It is also believed for the case to move to the Supreme Court in the future.

During this, the opinion of the Second Circuit gives various clarifications for the fair use test of the Copyright Act as to its application to the works of visual art. The Court recognised the criticism of recent cases of fair use like the Cariou v. Prince which was about the unlicensed use by Richard Prince’s of Rastafarians photographed images. The main issue seen here was whether too much weight was put on the question if the new use is “transformative” putting the other statutory fair use factors at the expense. The Court stated that all the 4 factors of fair use must be considered independently even if a new use is found to be changing under factor one of the test. The key question can be determined by the Court – “must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a ‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it”. The court provided these markers for artists -(a) an artist should not just merely apply their separate individual style to unlicensed work to compose a transformative work. (2) An artist’s intention to create something with a different meaning, is not relevant to the question of transformativeness. (3) Similarly, a judge’s or critic’s personal opinion of the message, intent, or the impression is not relied on to see if the work can be seen as a new meaning or message.

In this case, Goldsmith took the photograph at-issue of Prince in 1981 and owns the copyright. In the year 1984, Goldsmith’s studio licensed the photograph of the Prince to Vanity Fair for use for “an artist reference” to be given as an example which would be published twice in the magazine with credits given to the Goldsmith and no other use than this was permitted. Goldsmith now claims that without her knowledge, Vanity Fair artist Warhol used her photograph to make 15 other silkscreen prints and pencil drawings portraying the Prince. According to her, she states that she was not aware of the Prince Series until 2016 when Condé Nast published some of the images as a posthumous tribute to Prince. When Goldsmith came to the knowledge of the Series in 2016, she contacted the Warhol Foundation and tried to solve their dispute amicable and in a private manner, but was unable to. In 2017, the Warhol Foundation sued Goldsmith claiming –

- A declaratory judgment stating that the Prince Series is non-infringing

- A finding that the series is a fair use of the photograph

Goldsmith and her studio counter-sued the Foundation claiming infringement of copyright works and barring the Warhol Foundation from changing, reproducing, making, selling, preparing derivative works from, selling, offering to sell, publishing, displaying, or claiming copyright ownership of the Prince Series or any photographs of them.

The main issues in this case are –

- If the Prince Series of Warhol and the licensing and republication of the photographs infringes the photograph by Goldsmith, and

- If the Prince Series is eligible to be construed as fair use to dodge the liability of the copyright infringement.

On July 1, 2019, the District Court acknowledged a summary judgment in Warhol’s favour finding that the Prince Series was fair use and dismissed the infringement claims of Goldsmith. The decision was largely based on the finding that the Series is transformative because –

- Warhol prince series portrays the musician as an iconic, larger-than-life figure” in a style that is “immediately recognisable as a ‘Warhol,’” while the Goldsmith Photograph shows Prince as a “vulnerable human being” and “not a comfortable person”, and

- The Warhol Foundation removed all the elements which were protected under Goldsmith’s photograph for the copyright.

Goldsmith appealed this Court’s decision to the Second Circuit on the fact that the lower court did not use the fair use test properly. The Second Circuit decided and reversed the Court’s fair use was not appropriate and the Prince Series were not a fair use of the photograph by Goldsmith. They also put forward and took it to another step by confirming that the Prince Series works were considerably similar to the Goldsmith photograph, hence the copyright infringement. The decision of fair use by the Second Circuit was of the opinion to identify any errors in the judgment by the lower court’s findings and to clarify the legal standards for them. While applying the rules and clarifications, the court reversed its decision and then used the factors stating that the Prince Series was not fair use based on these factors –

- FACTOR ONE – The Purpose and Character of the Use. The lower court while finding the tranformativeness of the Prince Series erred and this factor favoured fair use because of the different aesthetic of the series, the series did not have the essentials of Goldsmith’s photograph and that the lower court based their decision improperly on the intent of Warhol rather than the reasonable perception of the series. The circuit also found that the works of Warhol were completely commercial in nature and serve a public interest that should be important to equitable relief.

- FACTOR TWO – The Nature of the Copyright Work. The lower court erred and relied on the transformativeness it found under factor one and hence ruled that the second factor did not favour any of the parties. Although Goldsmith’s photograph was not published and creative.

- FACTOR THREE – The Amount and Substantiality of the Use. The Circuit found that the lower court was incorrect in its finding that this factor favoured fair use because Warhol both quality and quantity-wise borrowed the soul and gist of Goldsmith’s photograph.

- FACTOR FOUR – The Effect of Use on the Market for the Original. The Circuit agreed with the lower court that the markets of the Goldsmith photograph and the Warhol’s Prince Series do not overlap and also found that this factor does not favour fair use because it would harm the potential of Goldsmith’s licensing markets including overlapping customer bases for the musician’s article. The court also went ahead to criticise the lower court for putting the burden on Goldsmith improperly instead of putting it on the Foundation as the party who is asserting fair use.

While on one hand, the lower court ignored the question of infringement and refused to decide on the substantial similarity of the Prince Series to the Goldsmith’s, the Second Circuit on appeal confirmed the facts that the works of both are substantially similar. The court while determining this used the ordinary observer test and decided that is not applicable to the Goldsmith photograph as it does not contain all elements of protection rather than the ones which are. The ruling for a definitive substantial similarity ascertains an infringement as the Foundation does not comment on to dispute if the copyright of Goldsmith is valid or not.

While determining, Judge Sullivan with Judge Jacobs agreed with the decision of the majority but also wrote separately to criticise the Circuit’s “over-reliance” on the question of transformative use. They put their major emphasis on the Fourth Factor – “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work” – which would create more clarity and predictability in the case law. 17 U.S.C. Section 107(4).

This case study has been authored by Deeksha Aggarwal during her internship with MikeLegal

References:

- http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2022/05/09/andy-warhol-foundation-v-goldsmith-the-supreme-court-revisits-transformative-fair-uses/

- https://www.firstpost.com/world/explained-the-copyright-row-over-pop-artist-andy-warhols-paintings-10506741.html

- https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/supreme-court-warhol-foundation-lynn-goldsmith-prince-lawsuit-1234623054/

- https://itsartlaw.org/2021/05/10/a-blow-to-pop-art/

- https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=73a9231e-93ee-49c1-b95d-bac7369efda5

- https://patentlyo.com/patent/2022/04/critics-role-fair.html